The source

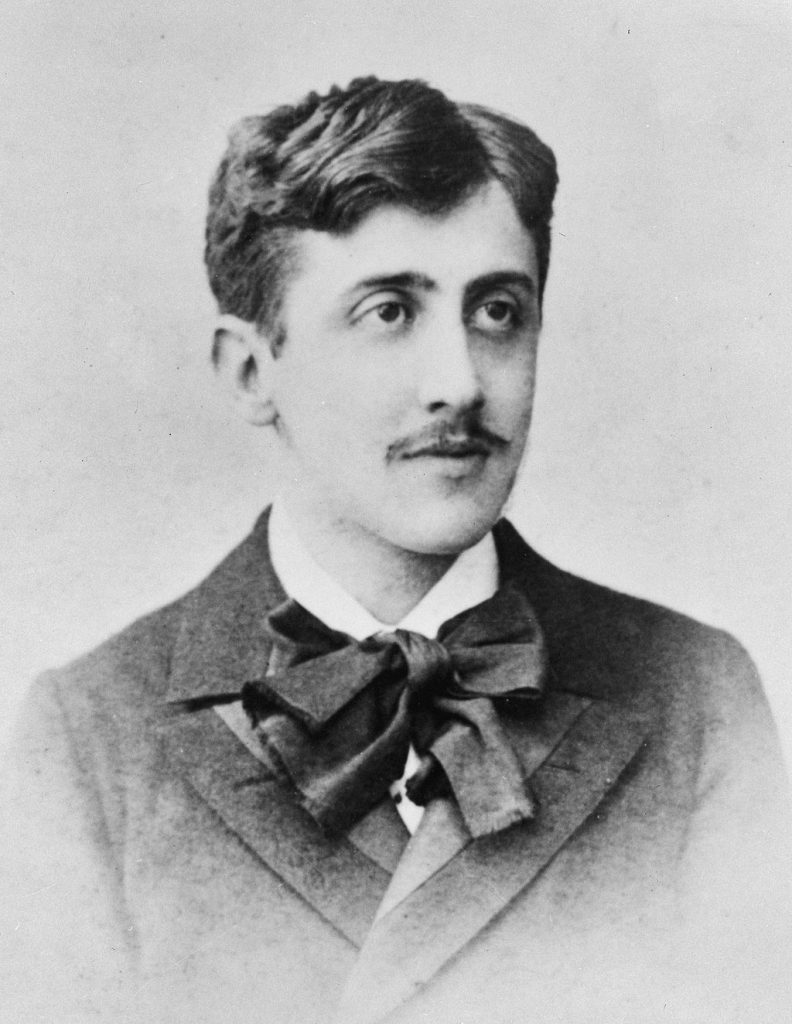

In Marcel Proust’s famous exploration of memory and meaning, In Search of Lost Time, the narrator remembers strolling as a child along the banks of the Vivonne river on Easter Sundays. The passage comes soon after the famous madeleine incident that first sparks memories of Combray, the town of his childhood, halfway through the first of seven volumes: Swann’s Way (SW, 1913).

In the same way that the taste of a madeleine softened in the narrator’s tea evokes strong, long-hidden memories of the people and places of his past, the section on the “Guermantes Way” conjures the route along the river into existence. The reader meanders through a description of water lilies and irises; young village boys catching minnows; the wafting play of light and shadow; and a window of blue sky passing over a boat.

As a child, the narrator never reaches the source of the river, which takes on “so abstract, so ideal an existence”, that it seems totally inaccessible. It is only when he is much older, in volume six, that he reaches the idealised point: “One of my other surprises was to see the ‘source of the Vivonne’, which I imagined as something as extraterrestrial as the entrance to the Underworld, and which was only a sort of square wash-house where bubbles rose.” (IV, p. 268)

Marcel is achingly disappointed with the river’s source, which becomes another measure of the distance between ideas and reality. However, Proust’s description of the river path has its own source, an earlier version, which does not disappoint.

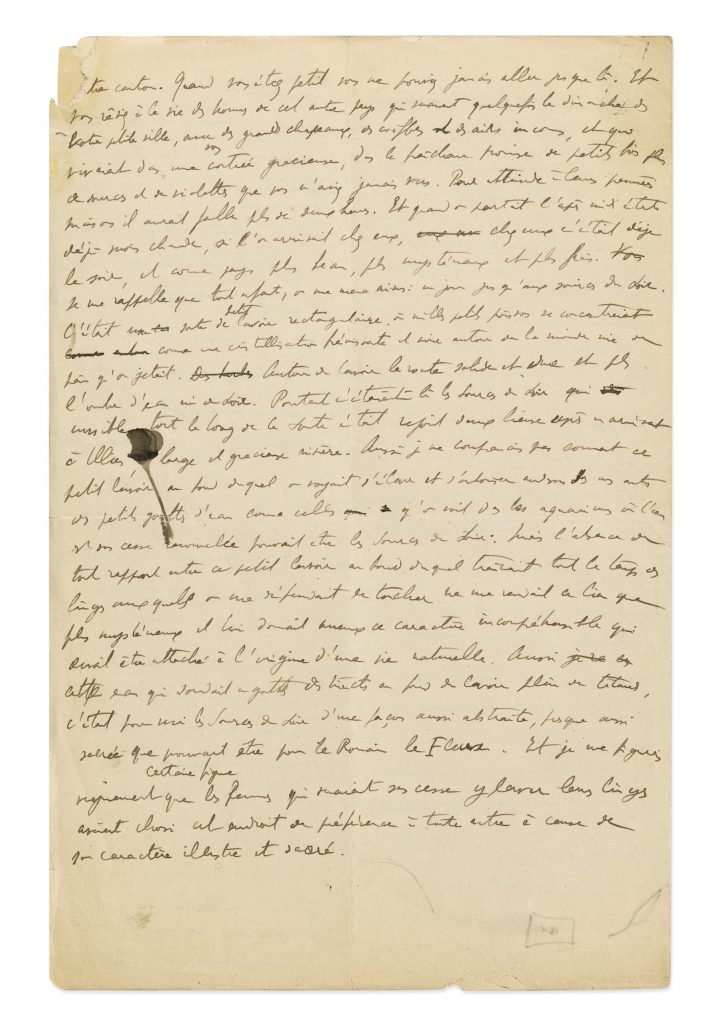

The Source of the Loir in Illiers (pictured below) is an avant-texte: a preparatory sketch for Proust’s river promenade. While previous estimates placed the manuscript between 1895 and 1903, a 2018 Sotheby’s catalogue entry suggests 1907-1908, at the time when Proust was developing his “autobiographical, introspective tone”. The manuscript is therefore a remarkable document of Proust’s experimentation and progression as a writer, revealing fascinating similarities and differences in the evolution of the novel.

The Source of the Loir in Illiers is an avant-texte: a preparatory sketch for Proust’s river promenade.”

Similarities

The most captivating similarity between Swann’s Way and the Illiers manuscript lies at the very heart of Proust’s creative output: intricate, descriptive sentences woven through with metaphors, which almost lose the reader before looping back to the central image. Often the passage starts with nature, only to reveal a deeply subjective vision of the world, human relationships and the self.

The Illiers manuscript begins, as in SW, during Easter Week, which Proust introduces with a scene of abundance and leisure. Birds flutter among the flowering cherry, apple and pear trees “just as impish, gifted brothers play with their small admiring sisters.” The long sentences attempt to capture the beauty of the scene and personify nature to reflect the narrator’s own feelings of joy. Similarly, one sentence in the equivalent SW passage, describing a field of buttercups “yellow as the yolk of eggs”, numbers 148 words in the original French. The sentence builds and blossoms into a meditation on the ungraspable nature of beauty – no matter how rich and enticing, you can’t eat a field of buttercups.

Aside from the language, Illiers contains the seeds of Proust’s childhood that he would finally plant in SW. The nineteenth-century train system increasingly connected travel and leisure, and led to a burgeoning crowd of day-trippers in fin-de-siècle French society. These local tourists, arriving from only a few miles outside the young boy’s village, represent the farthest reaches of the unknown in both versions below.

And you imagined the life of the people in this other land, who sometimes came to your little town on Sundays, with caps under large hats and foreign ways, and who lived in a gracious land, in the promising coolness of little woods full of streams and violets that you never saw.”

The Source of the Loir in Illiers

“Of Méséglise-la-Vineuse, to tell the truth, I never knew anything more than the way there, and the strange people who would come over on Sundays to take the air in Combray, people whom, this time, neither my aunt nor any of us would ‘know at all,’ and whom we would therefore assume to be ‘people who must have come over from Méséglise.’”

Swann’s Way

Differences

Yet while Proust continued to explore the sensations and assumptions of childhood, his writing increasingly moved from autobiography to fiction. Proust’s Illiers, the town of his summer holidays, becomes Marcel’s Combray; the real Loir river becomes the fictional Vivonne. Strangely enough, reality has come full circle: in 1971 the town was renamed Illiers-Combray on the centenary of Proust’s birth.

The main difference between the texts is that the narrator in this early version reaches, while still a child, the source of the Loir: “a kind of small rectangular wash-house where a thousand little fishes would throng in a black, quivering mass.” And despite the adult Marcel’s disappointment in The Fugitive, in Illiers the wash-house retains its awesome sense of mystery. The small wash-house, so separate from the idea of the river itself, becomes “as abstract and almost as holy as a certain figure of the River could have been for the Romans.”

In fact, we can trace the wash-house through other early manuscripts; Proust was a master-crafter, whittling his scenes into their final, sculpted form. In Pléiade, I, Esquisse LIII, the source maintains its mythical pull: “And I leaned in astonishment over this wash house where this immaterial and immense thing was: the Source of the Loir, where the door to Hell is located.” Other sketches show Proust trying out different names for the river, such as the Vivette.

Proust was a master-crafter, whittling his scenes into their final, sculpted form.

The imprint of the heart

By following Proust’s manuscripts to the source of his most iconic scenes, we discover more about his creative process. Yet we also have an idea of the lingering images of his childhood, the buried sensations that he would eventually build into his fictional autobiography, In Search of Lost Time. This masterpiece, widely recognised as “the most respected novel of the twentieth century”, was born from manuscripts such as The Source of the Loir in Illiers and the experiences of the great writer himself.

The Illiers manuscript illuminates the path of the Of Lost Time literary unit: following the river to its source. Letters and manuscripts are a written trail of a person’s life, shedding light on their world-view and relationships. As Proust does throughout In Search of Lost Time, we seek in letters and manuscripts, in the very handwriting of the individual, “the imprint of the heart and the traces of a life.”